Erasing

May 1st – May 31st, 2014: Driscoll Babcock Galleries, New York, NY

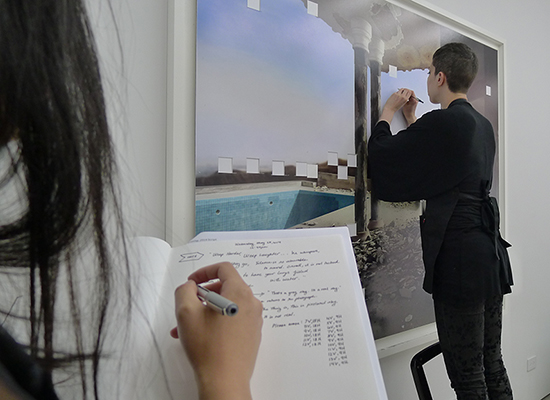

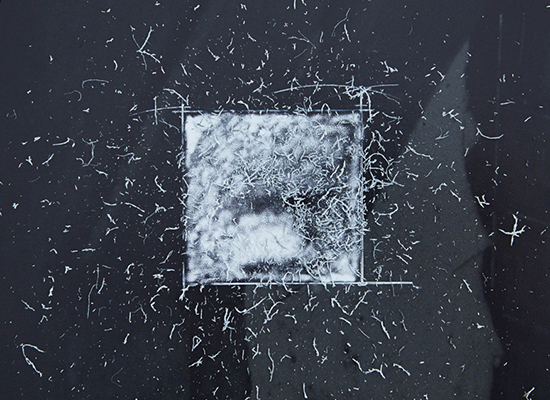

Erasing was a durational performance piece that consisted of a large display table, a set of archivist tools and an inkjet photograph approximately 58” x 77” in size. Each day, the artist ritually selected a cubic square of the image to cut from the photograph while an assistant documented the process. The tiny photographic squares were then pinned to the display table while floating above its surface.

The mounted photograph depicted a serene view of a palace with a swimming pool overlooking arid hills. It was a style of documentation common to home décor and real estate magazines that sought to accentuate the idyllic qualities of the mansion depicted. However, further study revealed that the palace has been plundered and destroyed. The view showed an empty pool overlooking arid hills, and the colonnade is crumbling. The photograph was taken in a palace that once belonged to Saddam Hussein.

In actuality, the mounted photograph was not the simple, straightforward documentation it first seemed. It was a reconstruction—a photograph of a set composed and stylized after an original press photograph of the pool by the palace. The original dreamily illustrated a palace of memory in an idyllic past, its destruction immortalized and filtered through an aesthetic haze. Its recreation suggested reclamation, empowerment, seizing control of the dialogue of the image and upending it. But to what extent? In the photograph, we saw the palace as an ideal, a monument to beauty and splendor. But it was also the home of a tyrant and dictator, a destroyer of the very ideals this palace elevates. The palace lay in ruins, but whose ruin? Did the palace represent hope renewed, the fall of a dictator whose monument to greatness has been shattered? Or was it simply a palace of Iraq, whose destruction symbolized its own fall from grace?

The photograph explicated none of these stories. Each day, the artist arrived to consider another portion of the image, deliberating on the aftermath of the palace’s destruction. In so doing, this process of selection and transference enabled further distortion through the filter of personal contemplation and transformed the image in both a literal and transhistorical sense. The story of the image and the history of its ruin are not one and the same, nor are the reconstructions of its aftermath. In the end, the image and its considerations were split—the war-torn and spotted terrain combined with the rippling landscape of scattered information were pinned to the table like so many dissected specimens of a past whose puzzle is incomplete.